One month ago I arrived with my carry on and my backpack in a tropical island in the middle of nowhere. Four weeks later, I think I have an informed idea of what digital nomadism really is, and whether it’s worth it or not. The answer? It might not be for everyone.

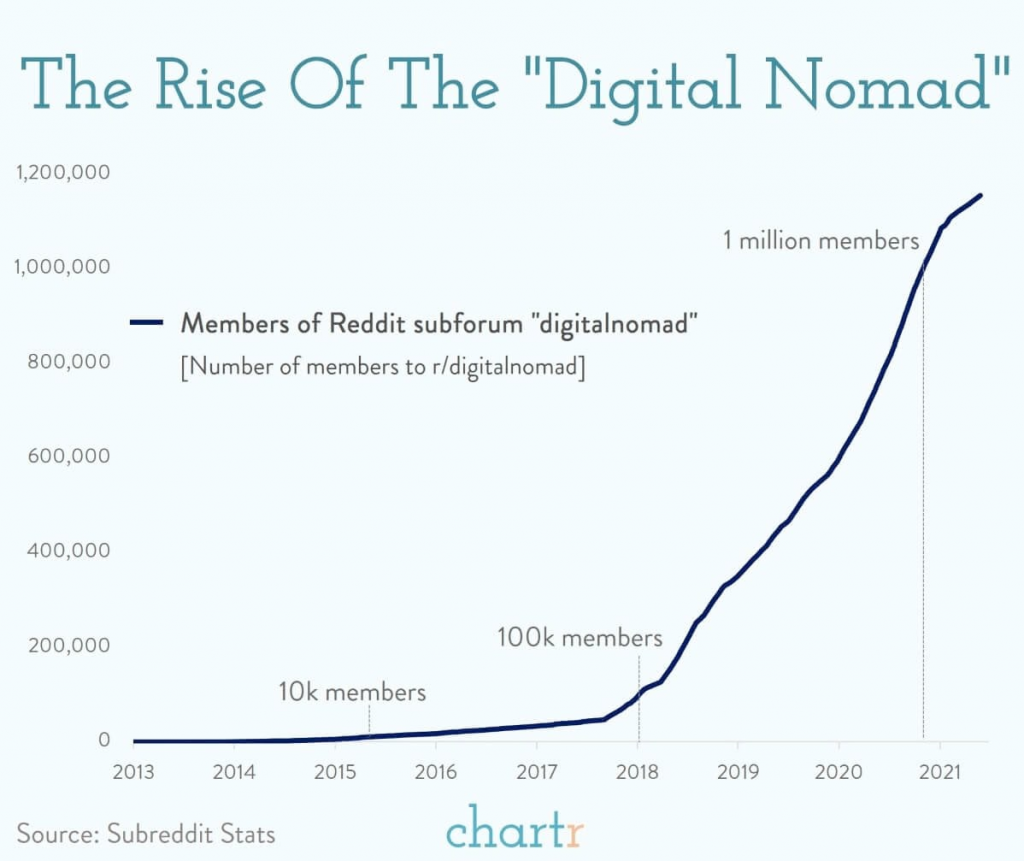

Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s great. But many seem to be idealizing and romanticising digital nomadism and remote working these days, especially as COVID-19 restrictions are lifting off and these trends are starting to boom. Every piece of content seems to focus exclusively on how cool it is to live and work from the paradise. The truth might be slightly more nuanced, though. Your typical perfect beach pictures on Instagram don’t often tell the full story, and downsides are about as important as upsides when you’re trying to make a decision on whether to go nomad or not.

Today I want to reflect on what I personally found after crossing half the world to live the experience myself. I’ll focus on two main aspects: the destination and nomading (traveling) itself.

Destination: Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia seems to be the archetypal answer to “where should I go be a digital nomad / remote worker?”. Practically, that means: Thailand, Indonesia, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

Reasons why this is the case are pretty much mainstream nowadays, but in a nutshell:

Why Southeast Asia

- 💸 Income arbitrage (earn money in a rich country → spend it in a poor country): This allows to live comfortably for ~$1k/mo total (which wouldn’t be possible in most first-world countries) – and/or allows to significantly extend your runway and multiply your wealth (i.e.: your money gets you way further). As far as I know, this concept was first popularized by Tim Ferris in “The 4-hour Workweek” back in 2007, which many would argue kicked off modern nomadism.

- 👨💻 Good internet speeds: most touristic tropical islands and mainland have fiber-to-the-home connection that guarantees 100+Mbps speeds, which is more than enough to work.

- 👮♂️ Relatively safe countries: unlike countries in South America – let’s take Venezuela for the sake of the argument – chances of being assaulted/kidnapped/robbed/etc. are pretty low here

- 🎉 Freedom lifestyle and lack of regulation: there are lots of fun/touristy activities to do + there’s much less regulation here, which in theory make these countries ideal for leisure. For example, anyone here can rent and drive a 800cc motorbike without even having a driver’s license. I’m not saying this is neither good or bad, and I know it sounds totally crazy by western standards, but that’s just the way it works here.

- 🚀 Asia is booming: a good friend of mine has been nomading in Asia for the past 8 years. He always says how everything is constantly growing, how different everything is now compared to 8 years ago. Especially cities. Like he feels there are a lot of things happening here in Asia, deeply transforming cities for the better – and we think part of that might be due to the aforementioned less strict regulations. From what I’ve seen in the past month, many things here look surprisingly modern, classy and sophisticated.

Seems like perfect life, right?

Why Asia is not the future

We have this running inside joke that “Asia is the future” in my group of nomad friends, because some of them like the region so much. It’s become a meme by this point, and we’ve started using the sentence to point out the things about Southeast Asia that are not so great. There are quite a few, and some could be a deal breaker for most. If you only read this part of the post and ignored the rest, you’d probably end up thinking Southeast Asia is straight unlivable.

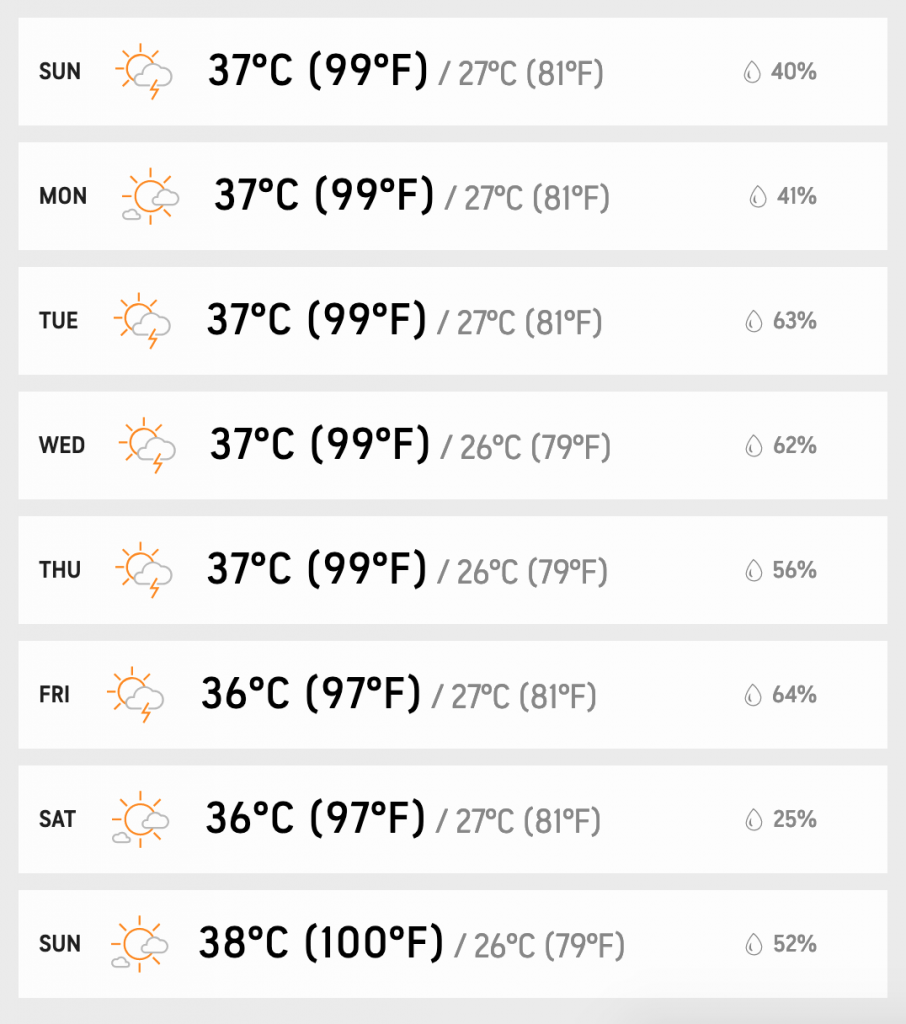

The heat

Oh boy, it’s warm in here. I was born and raised in Spain, and to me the average day here feels scorching, worse than the warmest day of Spanish summer.

I remember the first time I stepped outside of Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi airport and I got to feel the heat. It was like a slap in the face. It was not only sweltering, but also uncomfortably humid. It only got worse after I had the chance to go explore the city for the first time. I remember thinking Bangkok felt like the most hostile city I had ever been in. I walked for about 5 or 6 minutes before realizing I was already drenched and my shirt was even dripping with sweat.

Then I understood this was a city where you’re supposed to take a taxi to go absolutely anywhere, and that life is not supposed to happen outside buildings. You literally go from AC to AC. Here they don’t have this concept of just hanging out outside, like we’re used to in Spain. There are no sidewalk terraces, and there’s no casually going for a walk. Which causes (IMO) a significant decrease in social life – something I miss.

Bugs: many and big

I took a plane to one of Thailand’s many islands, and when I arrived in my Airbnb this little fella, the size of half my foot, was waiting in the corridor to greet me.

I managed to avoid him and opened the door, only to find my apartment was full of spiders. I dropped my suitcase and asked some friends about the bug situation here. They sent me a couple of short videos:

After this I went out for a while to get some fresh air, and a few steps in I crossed paths with a big ass toad. He was not scary, but it reinforced this feeling that I was in the middle of a damn zoo. I got back to the apartment to get my shit together and started hearing loud, high-pitched noises. I was not alone: I was roomies with one or two geckos that lived somewhere in the house behind curtains and under sofas.

I admit I freaked out for a while. A few years ago I think I would have noped the shit out of here. But what’s life without a bit of challenge to make you grow stronger, right?

Over the following few days I came to understand I was the intruder, not them. After all, I was in a freaking tropical island in the middle of the ocean: what the hell was I expecting? Everyone has geckos in their houses here. You even get them in the most high-end houses and villas: money can’t stop animals. I started normalizing the situation (after going through a few cans of insecticide spray to keep most creeping creatures at bay) – and that was that.

I won’t even get into the flying cockroaches and the huntsman spiders stuff, as it might be a bit too much for some readers. All I can say is you get used to it after a while. You start understanding Southeast Asia is a coliving where your colivers are insects, and you even start appreciating the beauty of it.

Welcome to the jungle

Literally. I think some friends laugh or think I’m lying when I tell them I’m in the middle of the jungle – but that, in the most literal sense, is true. These are tropical countries, covered by very dense jungles, and all human establishments are built amidst them. Streets were all dirt trails in the 90s, now most trails are cemented, but still – it’s a jungle with buildings in it.

By the way, the jungle gets really, really loud at night (because of the bugs chirping). Like, you could almost have trouble hearing someone talking to you if they were not right next to you. Yes, that loud.

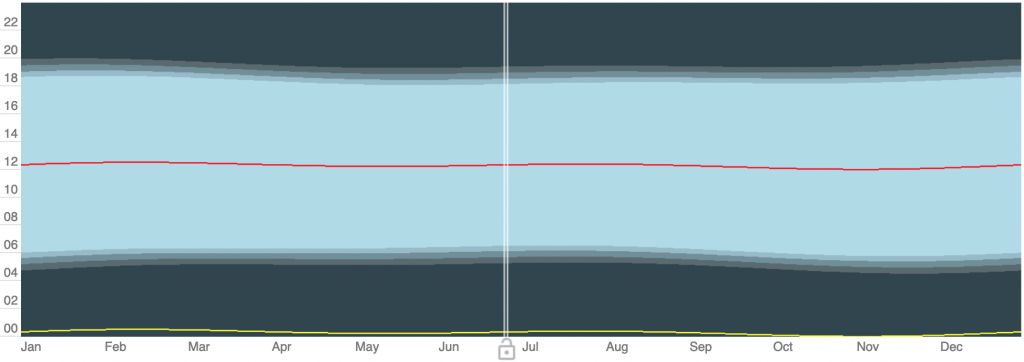

Early sunrise, early nighttime

Days start at 6am and end at 6pm, and because we’re close to the equator, this remains stable throughout the year. It may be not the best schedule for night owls like myself – if you wake up at noon you’ve already missed half the day. I’m really noticing the absence of light in my days (especially at this time of the year, when the sun sets at 10pm back home)

Excessive plastic

If you’re an environmentalist, you won’t probably like Southeast Asia. Everything is wrapped in plastic here. Even sausages are individually wrapped in plastic when you buy them in packs (and the pack is made out of plastic, ofc). Plastic bags come wrapped in plastic. Tap water here is not drinkable, so you have to constantly buy packs of big water bottles that are of course made out of plastic and come wrapped in plastic.

If you’re ordering food, it’ll come in plastic bags, with plastic cutlery, in plastic containers, with sauces and liquids contained in plastic zip bags tied with plastic rubber bands. If you buy coffee to go, it’ll come in a plastic cup with a plastic lid, with a plastic straw and with a tiny plastic bag to hold it. They do seem to recycle to some extent here, but we’ve also seen what seemed like multiple clandestine trash burning pits in the middle of the jungle. I wouldn’t really trust waste management procedures here.

You move across the world just to feel western again

There’s a contradiction I can’t stop noticing. We travel across the whole world only go to places (cafes, restaurants, apartments) that look European or American. We’re in Asia – but we’re looking for what looks western and modern. We’re after the same things we had back home, only half the price.

It feels as if we needed to travel to a third world country just to to live as our parents did our age. We could make the case that our generation is on average doing worse than the previous generation. Most people can barely afford their rent, let alone owning a house. Traveling to cheaper countries partially fixes that problem, and I’m not yet sure whether that’s something good or bad.

No speak English kap

I was already expecting this, but an American friend of mine found it shocking. People speak little to no English here. Best you can get is broken English, which I would argue is a language of its own. It’s both useful (you literally get to communicate more with less words) and harmful – a couple of native friends can already tell their language proficiency is deteriorating and their speech is starting to miss tints and colors.

Asian Broken English, as we might call it, is very characteristic. To speak it, you first need to drop stop words, mainly articles and prepositions. For instance, you would say: “Can I have coconut?” instead of “Can I have a coconut?”.

Then, you just simplify your sentences. The following sentence will get you nowhere in the supermarket:

“Excuse ma’am, I’m sorry in advance for the trouble I might be causing you, and I really appreciate your help – I couldn’t help but notice you’re wearing the official store uniform and I was wondering if you could point me in the direction where the coffee aisle is?”

Instead, I just go for a simple: “Sorry, where is coffee?”.

This is obviously an exaggeration. But it literally works like this, especially over the phone. If you’ve ordered food and your driver is arriving, they’ll call you and you’ll have this conversation:

– [unintelligible speech that sounds like “Hello, I’m nearby”]

– Hello. I’m outside kap.

– [unintelligible speech]

– Can, can. Come outside. Outside house kap. Can come now kap.

And within 10 seconds you’ll see your driver.

(Note: in Thailand, it helps if you end most of your sentences with “kap” or “ka”, depending on whether you’re a boy or a girl – it is just a formal particle that pretty much helps mark the end of a sentence)

Life outside big cities is primitive

This is not at all representative of all Southeast Asia, but since it’s been most of my experience so far, here it goes.

If you go to an island, even a well-known, touristic island full of 5-star resorts, you’ll notice there’s no such thing as a “city” here. There’s just one road with loads of precarious buildings on both sides, a monotony only disturbed by the occasional modern, luxurious, western-looking establishment we’ve already talked about.

There’s no urban planning whatsoever. There are no parks. There are no squares. There are no public spaces. There are no sidewalks. Most roads are just concrete slabs (if not plain dirt) on the middle of the jungle, most streets are unnamed and some routes on Google Maps are plain wrong. There are no neighborhoods, just scattered houses – many of which are notably poor (especially as you leave the main road and get into the jungle).

Your average Instagram post only shows what’s inside of fancy western-looking buildings, but misses the remaining 90% of reality that’s outside, which usually involves poverty and underdeveloped infrastructure. If it rains (which it does, almost every other day), you may get electricity and WiFi cuts. I’m writing this with my laptop running on battery power and using my phone as a hotspot, because power just went down.

On top of this, there’s this culture that locals call “island life”. It refers to the fact that the average state of things on an island is broken or malfunctioning. If you get mold in your AC they’ll reluctantly clean it in a very superficial way – and they’ll make you aware you’re requesting extremely high standards and that moldy AC is “island life”. If your AC is barely working and the air is not cold, they will say it’s OK, it’s “cold for island”. That’s island life.

But as I said earlier, this is not the case if you stick to big cities like Bangkok.

Don’t stay in Southeast Asia for too long, maybe

Something we’ve noticed is that it’s probably best if you don’t stay in Southeast Asia for too long. It’s totally fine to spend a few months here and there, but maybe not years at a time. This place is so different to what us westerns are used to that we’re worried living here could permanently end up messing with your way of perceiving and understanding the world (as if a relaxed, “lawless” island life became the new normal and the baseline to measure everything against). We worry it could maybe affect your judgement and effectively isolate you from the west by becoming increasingly more detached from reality.

All in all, Southeast Asia is great, but it also comes with major drawbacks one has to be aware of. In my opinion Asia might be the future, but it’s not the present – not yet at least. Southeast Asia feels like the west half a century ago. Which is great, because everything is developing quickly and that comes with loads of opportunities. But it’s also not quite there just yet.

Digital nomadism and traveling

As I thought about the pros and cons of Southeast Asia as the main destination to go be a remote worker, I kept finding myself questioning the whole travel-and-work-from-anywhere culture itself – what we may understand as “digital nomadism”.

I feel many people idealize digital nomadism nowadays, as if it were a new trendy, glamorous thing to do. Look, becoming a digital nomad is as easy as booking a plane ticket somewhere and just going there with your backpack, which for all intents and purposes is almost indistinguishable from good ol’ traveling. The digital nomad scene has more in common with the traditional expat scene than with anything else, I would say. But for the sake of this post, let’s stick to the modern concept of “digital nomadism”.

What’s not so great about nomadism

The initial shock

There’s a shared story among almost all nomads, and I find it very interesting that we’ve all been through this shared experience one way or the other.

It’s the typical “first time abroad” experience.

I experienced it most prominently in 2016, when I went live abroad truly by myself for the first time. I remember not wanting to leave my dorm room for the first few days when I first arrived. I was scared of not knowing how things worked in my new country, and scared to confront them.

The same pattern repeats itself across people, almost as if it was a exact copy of the same story. You arrive in a new place, get scared and spend the first week(s) locked in your hotel room because you don’t want to delve into your new unexplored reality.

It feels awful. Everything feels terribly hard.

Everything is chaotic, you don’t really know anything for sure, you don’t have any anchor points, you don’t know what to do and you don’t know what you don’t know.

The only thing I know for sure is that this feeling goes away sooner or later. And then things are okay. It’s been the same story for everyone. You just have to push through. One smart strategy might be to develop a stable routine.

Loneliness

Loneliness is intrinsic to nomadism, and I’d say one of its major drawbacks. I’m extremely lucky as I’m traveling with friends, but here’s a pattern I’ve realized:

When you travel you have –by definition– an unstable, ever-changing environment. You don’t really belong to any local community. And most notably, you are likely not to have many lasting friendships. There’s few to no nomad friends you’ll be able to maintain across cities and countries. You’re forced to make new friends every few months, and every new friend you make is likely to leave as soon as their visa expires or they decide to go to the next spot.

The notion of friendship is redefined in nomadism: I feel it becomes more of an utilitarian concept – rather than a strive for deep, long-term relationships.

The local environment and topography also plays a huge role, interestingly. You could be living a just a few kms/miles apart from your friends, but if the terrain is mountainous or not walkable, that’ll mean a 10-15min bike ride at least – and that’s a high enough cost not to see your friends that often.

Lifestyle first

Many nomads live and die for the nomadic lifestyle. That is, their main “goal” is to be a nomad, explore the world, get to know different cultures and keep traveling. Everything they do, they do to support this goal.

What you do professionally becomes almost a necessary evil to finance your travel lifestyle.

I don’t necessarily agree with this mindset. I find it more difficult to create deep, meaningful, relevant work if your focus is somewhere else. I feel nomadism tends to create lifestyle businesses more than anything else, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

It’s understandably so, though. Nomads can live off ~$1k/mo, and once you’ve created a business that yields, say, $5k/mo and you live like a king in a big house with private pool, why would you give up on that comfort and stability? It’s a way too convenient position to leave for anything else that might not work out. A poor man’s golden handcuffs?

If you’re trying to create a billion dollar business with potential to change the world, I’d argue doing it while being a nomad might not be the best strategy for you. It might be ideal to start out, though: being constantly on the go, feeling the pressure to make things work and constantly changing your environment to expose yourself to new ideas can definitely have a beneficial impact on helping someone get things off the ground for the first time.

The people you meet

As a consequence of most nomads pursuing a lifestyle rather than a career, you get an interesting effect: you meet shady people.

Since “everything goes” as long as you make enough money to pay for your traveling lifestyle, many people here make their money in more shady ways. I was told that ten years ago the main trend was to become an email spammer, and just a few years ago “dropshipping” was the thing to do. Nowadays I feel it goes more along the ways of doing web scraping or automated marketing in the most general sense. I think there’s also a fair deal of crypto traders and SMMA (Social Media Marketing Agency) kids.

Here you’re not likely to meet the kind of tech geniuses you get in Silicon Valley. Or the kind of top 1% performers you’d get in any other expensive city like NYC. These places act as a natural filter, and only the people that make the cut can afford to live in there.

When you’re a nomad, you go after cost efficiency. The countries you go to are generally cheap, so they attract people that can’t really afford living in EU/USA. As a consequence, these places don’t act as a natural filter, since there are no entry barriers, and you may encounter more less-than-average performers.

You also get a confluence of diverse travel motivations.

Some people travel to find themselves. These are people that feel lost in life, generally in their late 20s, that take a year off to travel, experience things and find meaning. Thus, I believe you’re more likely to come across lost people when nomading, rather than people with a clear goal and well-defined life strategies.

And on top of that, it’s not only nomads you meet. Digital nomads are still a tiny proportion of all travelers – so most people you’ll cross paths with will not be nomads. There are a wide variety of different strains of travelers, and there are many diverse subcultures going on at the same time, many of which are sketchy by nature. I’m talking about sexpats, begpackers, modern hippies, drug abusers, etc.

It’s only understandable this is the case. The origins of all these scenes date back for decades, probably way back to the original hippies in the 60s, even earlier. There’s a really good documentary that explores how now-nomad spots were full of backpackers doing drugs, trying experiences and testing their limits in the 90s, and it’s fascinating to see the overall landscape hasn’t changed that much. They all went there to live and have fun for cheap. Then Tim Ferris refined and popularized this set of proto-ideas in the 2000s, making them palatable for a more mainstream audience, and turning them into something noble to do – and a few years later you get what we know today as “digital nomads”. (If you’re interested in reading more, Pieter Levels from NomadList did a much better job at outlining the history of the movement here)

Context switching is very costly

When people say they love traveling, they don’t probably mean what you think they mean.

People love the feeling of being in a different place, yes – but actual transportation and administrative work (visas, plane tickets, insurance, finding housing, a gym, a bike, etc.) accounts for the majority of what “traveling” really is.

Traveling is really costly, and I’m not talking about money necessarily. The real cost of traveling comes in the form of context switching.

Context switching is among the most taxing, energy-consuming things you can go through. Context switching is not good for the psyche: your brain loves a good routine and needs plenty of time to adapt to new environments. Your brain was not designed to live in a constant state of chaos. You only need an optimal amount of unfamiliarity at any given time, enough to challenge you and make you grow. Too much unknown and you’ll feel lost and stop functioning at full capacity.

What me and the friends I’m traveling with have noticed is that it’ll take us somewhere between 2-4 weeks of low to zero productivity before we figure out each new place: accommodation, gym, supermarket, cafes/cowork, schedules, etc. – and before we feel comfortable in the new routine. That’s a month worth of time wasted per trip, and it quickly adds up the more you move. Before you realize it, half of your year is gone in non-productive adaptation periods.

Thus, a new movement is gaining popularity lately, up to the point of becoming the de-facto nomad modus operandi: the rise of the slowmad. Most nomads will only travel 3-4 times per year, every 3-4 months. The notion that most nomads travel every few days or weeks is probably wrong. But most of us are still forced to keep moving and changing places to some extent because our visas run out. Only nomads that manage to get a long-stay visa overcome this problem.

When traveling becomes stale

When you’ve been traveling for too long, the whole traveling thing can become stale and you no longer want to do it anymore. This is often described as no longer being excited to go to new places, and/or feeling like every new place is a replica of the last one.

I only know about this because of stories I’ve heard from nomads that are way more experienced than me, but I’m already starting to understand why.

As my friend Dan puts it: 90% of the time you’re gonna be facing a white wall, either in the US or in Thailand. It’s only the remaining 10% that’s different from country to country.

If you don’t make that 10% count, you’ll no longer feel like you’re traveling, and you’ll start wondering why the hell are you traveling in the first place if every place is the same. You need to go out on excursions and do activities, because otherwise it feels like it doesn’t matter where you are, since you could be anywhere. Finding the right balance between pleasure and work matters even more when you’re a nomad.

I think one common mistake is trying to deal with unhappiness by moving to the next place. It may be important to learn how to be happy with your current circumstances, whatever they might be, or you’ll risk forever chasing something that you’ll never reach, because there always is a next place to go.

What’s great about nomadism

With so many downsides, it could look like there’s no upside to being a nomad remote worker – which couldn’t be further from the truth. I just wanted to cover the negative first, but I’m in love with nomadism so far, and I think there’s a good bunch of reasons to go take a plane and do the nomad thing.

Personal growth

This is so cliché I almost hesitated to get it in. But hey, it is true. When you’re traveling so often you’re constantly going out of your comfort zone, doing things you’ve probably never done before, meeting people from backgrounds you could have never met otherwise… and I just think that’s extremely valuable, and it makes you grow as a consequence. You discover there’s more to you than you think there was.

With every trip, and with every new thing you discover you were wrong about, you develop your character and become a more well-rounded person.

Traveling changes you, and you change as you travel. I even have one friend that suggests that since you’re going to new cities often and you’re meeting a completely new set of people every couple of months, you can just go ahead and try out different personalities. His point is that you could try and play out different traits you’ve always wanted to try in yourself, or exaggerate traits you currently have, and see what you feel more comfortable with. I felt this was a really interesting idea, and a really good way of proving that traveling can actually change you.

Slow down time

When you’re constantly on the go and need to reevaluate your whole life every few weeks, it feels like so much stuff is happening, and months often feel like entire years.

Some say that’s the trick: as you get older time tends to go by faster, but you can slow it down by traveling. It definitely holds true for me so far.

Spice things up

I’m not necessarily talking about the food you’re likely to eat in Asia (although it is spicy as hell). But changing contexts regularly –despite being extremely costly– will shake things up, which will likely help you overcome creative blocks and will help you produce new, original ideas.

I believe something important in life is that you don’t want to get too comfortable – ever. If you do, you start being complacent, which may lead to you getting stale and dying (creatively speaking). And I think nomadism is great to avoid that.

Lifestyle

One of nomadism’s handicaps is also one of its major advantages. You risk putting too much attention into the nomadic lifestyle, true, but the fact that this lifestyle is great is undeniable.

I’m living in a big villa in a private neighborhood. 2 floors, 3 bedrooms, private garage. Rent is $490. Gym, sauna and swimming pool are included in the price.

I have friends living in luxurious villas with private infinite pools overlooking the ocean, for the average price one could be paying for a small 1-bedroom apartment rent back home in a first-world big city.

Big, modern cities

There is poverty, true, but you also get these immense, modern, incredibly developed cities like Bangkok. These cities look like nothing I’ve seen in Europe, they are maybe only comparable to cities like New York or Chicago. Things are expensive in big cities, but in return you get this “back to the civilized world” feeling.

You’ll still see hints of poverty in side streets, and you may get a cockroach or two even in a 4-star hotel, but overall you don’t get most of the “island life” culture.

Perfect playgrounds

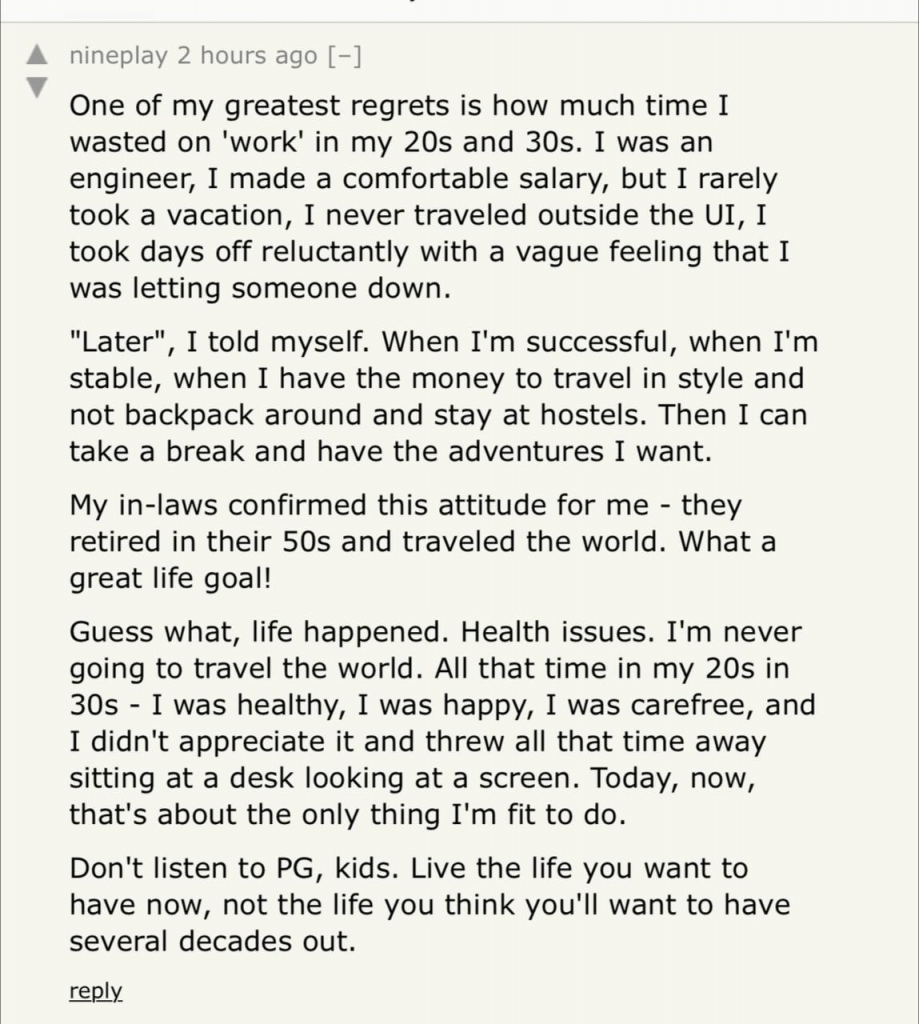

Everyone says you should use your 20s to try everything and figure out what you like. And I can’t think of a better way to do that than going nomad. You can try almost anything, in the most literal sense. And there’s almost no downside to it, except of course opportunity cost.

You can test how it feels to live like a millionaire for the price of an average rent in San Francisco, and see what’s it all about. Or you can go all the way to the other extreme and live in an open hut in the beach with no bathroom nor electricity. Or in a $50/mo condo. Everything is out there for you to try.

Plus, I think there’s a really powerful case to be made that you should do this in your 20s and 30s, instead of (or before) going all-in in your career, settling down and maybe starting a family. You might never do it later otherwise:

Remote is the new Silicon Valley

I know I said the nomad scene tends to create lifestyle business only – but I also feel something very fresh about this whole thing. Feels as if a shift in mentality were taking place, and remote could become the next Silicon Valley.

I can see how this is could be the next big way of building startups. Pieter and I have talked about this for a while, and it feels as if we were in the early days of a massive future trend. We can’t obviously tell, but we often compare it to how the 2005 SF startup vibe must have felt, with YC being born sparking a whole new generation of entrepreneurs. Feels like up until now, there’s only been a handful of successful nomad entrepreneurs that are discovering and setting the rules on how to build companies while traveling and working remotely. But many others could follow in the future and take the scene to a whole new level.

Conclusion – Will I continue to be a digital nomad in Asia?

If you do a quick search for “paradise” in Google Images, most pictures you’ll find are just what I’m seeing right now as I write this, and what I’ve been seeing on a daily basis for the past month.

But this is not paradise.

These are not better countries. There are just different countries, and each one comes with a different set of problems.

You can choose which set of problems you want to deal with, but you cannot choose not to have any problems at all.

Everything is cheaper here, and you could potentially live a luxurious lifestyle – but in turn you also get heat and insects.

Back in Europe you don’t have to worry about your AC being moldy and the technician not wanting to clean it – but in turn you also get a hyper-regulated market where innovation is stagnating and dying. Everything is a tradeoff.

All in all, I will continue to be a nomad in the foreseeable future.

But there’s a pattern I’ve noticed among nomads: they tend to travel for ~1 year, and that seems about the average length most are willing to withstand context switching for. After that year, they either settle in a place they’ve liked – or they go back home.

I don’t see myself nomading for many years, but who knows. What I do know is that these experiences are always net positive, and no matter the final outcome – you always come out stronger on the other side.

Limitations of this post: I’ve just been here for a month. And I’ve just been to Bangkok and an island – having spent 90% of my time in the later. My experience might be both incomplete and biased towards “island life”. I should live in big, well-developed cities like Seoul, Tokyo, Taipei or Shanghai before I get a more objective and balanced understanding of what living in Asia really looks like. Also – when I talk about “Asia” I’m most likely referring to Southeast Asia exclusively. I’m very much aware rural Thailand is nothing like South Korea or Japan.

P.S.: I already wrote about going nomad a couple of months ago. Strictly speaking, I’ve been nomading since February. But I don’t think those first months really count. Back then, I just took a 45-min flight to a nearby country close to my hometown (MAD ✈️ LIS). A country in which they even understood me if I spoke my mother tongue slowly enough. I don’t think that really counts as actually doing the nomad thing. I was too close to home, in a culture that was almost identical to mine, speaking a very similar language. It was way too comfortable. Every nomad story I came across had this intrinsic notion of going to a far place with a very different culture and feeling shocked – so I think it’s more fair to say I only became a nomad last month.

P.S.: Follow me on Twitter to stay in the loop. I'm writing a book called Bold Hackers on making successful digital products as an indie hacker. Read other stories I've written. Subscribe below to get an alert when I publish a new post:

This is very well done. I think 6 months of being a nomad will give you a more well-rounded perspective. Looking forward to it.

I wished you had started the post by saying you are only a nomad for a month ♂️

I’m not sure I understand you – the post is literally titled “What I learned in my first month as a digital nomad” and starts with the sentence “One month ago I arrived…”

Interesting perspectives. Would be interested to hear how it goes for you moving forward.

Have been doing the same for 4+ years now and most of the negatives you stated (particularly as they relate to SE Asia) don’t really factor in my opinions any more. They’re just part of what it’s like to live there, and by choosing to do so I am accepting both the good and the bad. As you say, there’s no better places, just different ones.

“ It can affect your judgement and effectively isolate you from the west by becoming increasingly more detached from reality.” – I feel as though having spent most of my life in Europe, spending some years away from it actually broadened perspectives considerably. For me, it’s less about being isolated from “the west” and more about being isolated from going back to single-location living anywhere in the world. I think successful nomads (who do it long term) end up with a total inability to commit to a place. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but it’s what I’ve observed.

Just spent a year in Thailand on a long-term visa. Had more opportunities to integrate into the community, give something back, volunteer, etc. It was great. But guess what, I’m on the move again.

Really interesting point of view, thanks a lot for your thoughtful comment. I 100% agree with the broadened perspectives point – especially if it’s the first time you’re abroad. That can be so beneficial for any individual. I still see a risk in going all the way to the other extreme, though. The sweet spot is probably somewhere in between.

I also wonder what my perspectives will be when I’m 6-12 months into this adventure. My guess is that I’ll become closer to your “inability to commit to a place” and “the negatives (…) don’t really factor in my opinions anymore” stance. How close – that I don’t know yet.

The part about “don’t stay in Asia for too long” is super tone-deaf.

How so?

Good article. If you think SE Asia’s challenging I should tell you all about what it’s like in Kenya.

So I’ve become an accidental nomad and would say I am between 2-8 months in. I lived in London for 7.5 years (Born and raised in Australia with an Irish passport) and then completed a 6 month stint working in Berlin. I’ve been in Portugal for six weeks and I’m heading to Belgium with a view to moving on a few weeks later. Everything in your article resonated strongly with me except the Asian experience (as I’m in Europe) and I’m 50 with a remote contract so not the demographic of people traditionally doing this or meeting the start up crowd. Remote work has me on a magical mystery tour attempting to work out where I wish to live long term and as an older person. So I’m trying to experience different places while taking advantage of my ability to move around with my work. I wonder if you have come across people looking for a location to call home and buy a place in Thailand? I will say, I know where I’m not keen to settle where I have been for various reasons although each place has been interesting and worthwhile. I’m also a little envious of your ability to experience this journey with people you know – a tribe of sorts. I think nomading with a tribe while it would have some stressful moments would ultimately make the experience somewhat easier? Thanks for the article share, very timely for me.

This was a really insightful post, well done!

Curious what your thoughts are on the “new” breed of digital nomads, e.g. normal, 9-5 office workers taking month-long trips. I don’t think this counts as nomadism, but it’s a significant blurring of the lines between travel and work.

E.g. my girlfriend and I spent 6 months in different cities around the US since our corporate jobs don’t allow us to work internationally.