Here’s a pattern I’ve been noticing lately: people often take way too long to make hard decisions because they’re hoping bad things will miraculously disappear or change on their own.

The problem is things don’t usually change significantly after a tendency has already been developed.

People wait too long to act because they feel they need more information about the problem. But my intuition is that most decisions can be correctly evaluated with >95% confidence in less than 3 months. I’d even say 4 weeks is enough to make a reasonably well informed guess about most things, but 12 weeks feels like a safer spot, just to be sure.

This rule applies to most things in life, to most difficult decisions: starting/leaving a new job, starting/ending a relationship, hiring/firing a new employee, starting/closing a new business, launching/killing a product.

Things take a relatively small amount of time to reveal their real tendency, and it is unlikely that tendency will ever change after it’s already been established. Generally speaking, things always tend to stay the same. Big changes require a lot of energy, and systems across the universe always tend to their lowest energy state. Introducing drastic changes could easily alter the state of equilibrium of the system and thus are highly unlikely to happen, as they would threaten the very existence of the system.

The default tendency of things is staying the same, not changing.

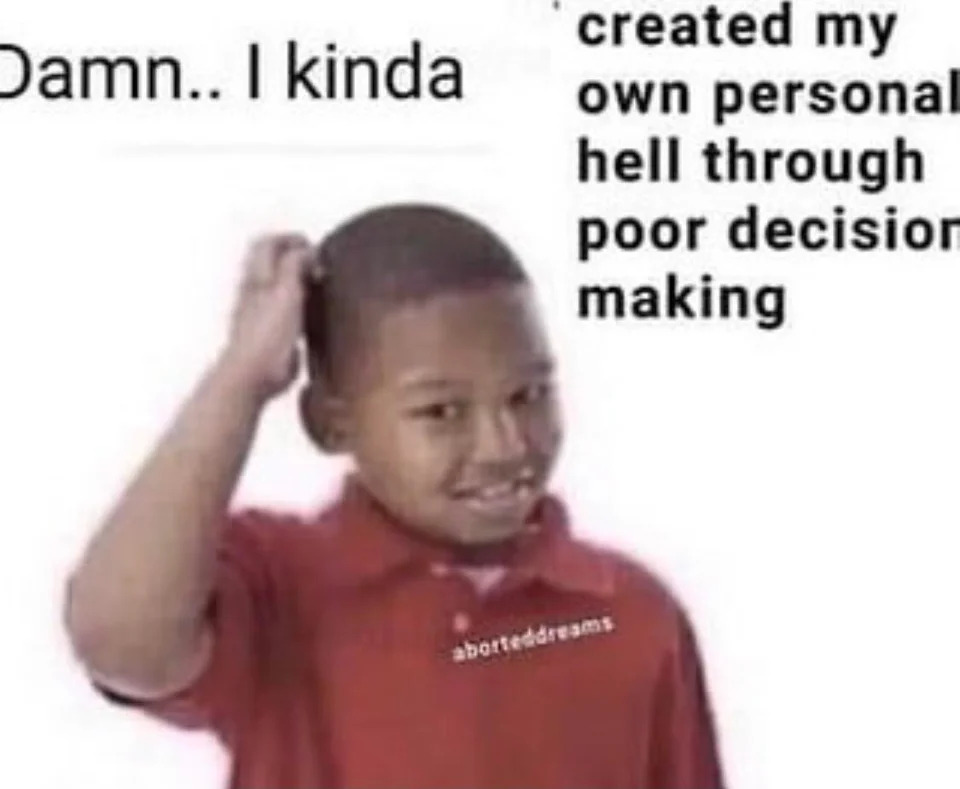

People like to think things will change on their own because the only other possible option is to go ahead and change them themselves, and that’s painful.

Hard decisions often require conflict, and conflict is not something desirable. Most people avoid conflict, which is why most people avoid making hard decisions ever.

This applies to all sorts of things, like starting a new job. Let’s say you’ve just been hired for a new position in a company. After 8-12 weeks, you’ve seen more than enough to know what working there feels like. Let’s say after 12 weeks you don’t like it: the job is making you feel miserable, your teammates are not be what you’ve expected and the tasks you’re doing are not what the job posting advertised. Yet you find yourself thinking a pretty irrational thought: “well, let’s give it at least one more year and I’ll make a decision then”.

Let me break the news to you: it won’t (probably) ever improve. The only reason you want to delay the moment of truth is because you’re afraid of making hard decisions, and also probably afraid of what will future recruiters think of you when they see that hole in your resume. I think that’s bullshit. You’re losing way more than you’re winning by keeping yourself in a bad situation like that. And there’s nothing to compensate such a net loss.

Some will say: “But you’re not giving it enough time. If you do this with everything, you’re never going to find something you like.”

I think that’s a fallacy.

After 8-12 weeks, you’ve likely already gathered 95% of the information there is to gather about the thing in question. If you had all the info you have now before accepting the job, would you still had taken it? If the answer is no, you should leave immediately.

Waiting one more year is one of the worst things you could do. One year from now you’ll be in the exact same spot, with very similar insights and conclusions, but with a great difference: you’ll have wasted one whole year of your life you’re never going to get back. Time is very limited. Time is the only asset you can’t get back, unlike money or status. If you want to optimize for something in life, I’d say optimizing for time is probably the best option.

Look, it’s highly unlikely you’ll hit any target on the first try. This applies to almost everything in life. You always need several tries, maybe dozens, until you find the sweet spot. If you prevent yourself from making very hard decisions quickly you’re effectively avoiding the necessary learning curve. Your brain needs a fail-learn-repeat cycle in order to improve. Sticking with a first mediocre decision is setting yourself up for long term failure (and most likely, a life full of misery and resentment).

Look at it this way: if you had 1 hour to test 100 different dishes and decide the one you like the most, what would your strategy be: (a) spend 50 minutes eating one single dish you initially disliked, hoping that it’ll improve the more you eat it until you realize you can’t physically have any more of it; or (b) try a bit of every dish, stopping immediately after trying something you detest?

Or say you’ve never done archery before and you have 1 hour to come up with your best shot. What would you rather do, (a) spend 50 minutes measuring everything compulsively trying to get a perfect first shot; or (b) going over the few initial shots as quick as possible, knowing that they will probably be shitty anyways, and that each failure will bring you closer to hitting the bullseye? You have to fail fast to learn equally fast.

I’ve had to go through a good deal of difficult decisions in the past few years, and they all follow this same pattern. The last decision of this sort I had to make had to do with me putting a lot of energy getting involved into something and then having to leave it almost immediately because it made itself pretty clear it would cost me way more than what I was going to get out of it.

If you look carefully, you almost always can spot the red flags from the very beginning. What happens is we choose to ignore them, because having to deal with them would imply not only admitting we were wrong in the first place, but also accepting we had lost everything we had invested.

This is the typical sunk cost fallacy effect. This fallacy basically makes people believe that previous investments (sunk costs) justify further expenditures. In other words, its like seeing a gambler in a casino roulette keeping wasting money hoping the next bet will make them recover everything they’ve already lost so far.

The optimal strategy is pretty obvious when you examine the situation objectively: if something is consistently making you loose more than it’s making you win, stop immediately and accept you’ve lost everything you’ve invested. It’s better to stop early and lose only X than to keep wasting resources and end up losing 100X. These are not typically win-win scenarios, but rather the kind of situations where all you can aim for is to minimize damage.

Trying to make the thing work is not a very smart move either. We’ve already gone through it: things are difficult to change.

And even if you could make it work by changing it somehow, it will probably make much more sense to use all that time and energy into something new anyways. That’s probably the best use of your resources, the one that maximizes your expected outcome. So I’d advise to stop trying to change things that don’t even want to be changed and put all that energy into building something anew, or finding a different person, or joining a whole different thing, or whatever your use case is.

Doing so will feel wrong, though.

Say you’re leaving a job you just got into but you don’t like. It’ll probably feel something like: “so we’ve gone through this very lengthy process, we’ve both invested a lot of time, effort and money into making this happen and just when we’re getting started you say you’re leaving?”. Feeling like a traitor and an ungrateful bitch is to be expected.

But that’s just not the case. Something all of these situations have in common is that before getting into any kind of commitment, both parties knew there were no guarantee of it working out. Just like there’s no guarantee you’ll like a film when you first see it on Netflix and are about to watch it. If you start the film and one third in you can’t stand it anymore, it’d be dumb to keep watching and lose the remaining hour. You just stop watching and switch to the next best movie.

It’s useful to think of it this way: in reality, you’re doing them a great favor by leaving early instead of being the elephant in the room and a pain in the ass for months or even years to come. Better lose “just” 3 months than 3 years.

When you’re playing long-term, losses in the short term quickly start becoming irrelevant.

TL;DR difficult decisions can often be made in much less time than we think, so it may be a good strategy to make hard decisions very quickly despite the perceived risk.

P.S.: Follow me on Twitter to stay in the loop. I'm writing a book called Bold Hackers on making successful digital products as an indie hacker. Read other stories I've written. Subscribe below to get an alert when I publish a new post: